QUICK REFERENCE

Date: December 28, 2025

Liturgical Context: Feast of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph

USCCB Readings: https://bible.usccb.org/bible/readings/122825.cfm

Readings:

- First Reading: Sirach 3:2-6, 12-14

- Responsorial Psalm: Psalm 128:1-2, 3, 4-5

- Second Reading: Colossians 3:12-21 (or 3:12-17)

- Gospel: Matthew 2:13-15, 19-23

One-Sentence Theme: God incarnates into our household systems, honoring the family as the first church where covenant identity is preserved not in stone but in the living relationship between generations.

INTRODUCTION TEXT, which you are welcome to read aloud before the Liturgy of the Word, is placed at the very end of this post.

THE READINGS IN CONTEXT

First Reading: Sirach 3:2-6, 12-14

When & Where: Written in Jerusalem around 200-175 BCE by Yeshua ben Sira (Jesus son of Sirach), during a period of intense cultural pressure when Hellenistic values were threatening Jewish family structures and covenant identity.

What’s Happening: Ben Sira is teaching wisdom to young Jewish men who are being pulled toward the Greek gymnasium culture – a complete educational and social system that devalued Torah study, ancestral wisdom, and the authority of parents to transmit covenant identity. The Hellenistic paideia (educational formation) competed directly with the Jewish household as the primary place of formation. Just as today we see schooling system claiming increasing authority over moral and ethical formation, ancient Jewish families faced Greek institutions that offered economic advancement, social status, and cosmopolitan identity – but at the cost of the particular covenant relationship with the God of Israel.

Key Insight: “God sets a father in honor over his children; a mother’s authority he confirms over her sons” – this isn’t about patriarchal control but about preserving the generational transmission of covenant memory. In Hebrew tradition, the word for the tablets of the Law is luchot awanim (לוחות אבנים). The word “stone” (ewen) can be read as “ew” (אב = father) and “ben” (בן = son). From the beginning, God was teaching us that the commandments are preserved not in the strength of stone but in the living relationship between father and son, between generations. The family is the place where we learn to say the Shema, where we remember the Exodus, where covenant identity lives.

Responsorial Psalm: Psalm 128:1-2, 3, 4-5

When & Where: One of the fifteen “Songs of Ascent” (Psalms 120-134) sung by pilgrims journeying up to Jerusalem for the three annual festivals – Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles. Likely composed during the post-exilic period when the restored community was rebuilding both Temple and family life.

What’s Happening: Pilgrims are ascending to the Temple, singing of the blessings that flow from “fearing the LORD” – that covenant reverence that shapes all of life. The psalm connects family flourishing (fruitful vine, olive plants around the table) with Temple worship (“The LORD bless you from Zion”), showing that household and sanctuary are intertwined.

Key Insight: “Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine in the recesses of your home; your children like olive plants around your table” – the imagery roots blessing in the intimate, hidden spaces of family life. The “recesses” of home are where covenant is lived daily, not just performed liturgically. The blessing flows from Zion (the Temple) but is received and embodied in the family gathered around the table.

Second Reading: Colossians 3:12-21 (or 3:12-17)

When & Where: Written around 60-62 CE to the Christian community in Colossae, a city in the Lycus Valley of Phrygia (modern-day Turkey), about 100 miles east of Ephesus. The community was likely founded by Epaphras, Paul’s co-worker.

What’s Happening: Paul (or a Pauline disciple) is addressing early Christians navigating how to live as covenant people within Greco-Roman household structures. The “household code” (vv. 18-21) was a common form in Hellenistic moral philosophy, but Paul transforms it with the phrase “in the Lord” – these aren’t generic social rules but relationships lived within Christ’s resurrection reality.

Key Insight: The passage opens with σπλάγχνα οἰκτιρμοῦ (splanchna oiktirmou) – “intestines of compassion,” a visceral, embodied mercy that feels in the gut. This isn’t sentimental emotion but the deep, somatic knowing of connection to another’s suffering. Paul then gives mutual commands: wives/husbands, children/fathers, each with reciprocal responsibility. The household code isn’t about hierarchy-without-accountability but about mutual self-giving. Crucially, “Fathers, do not provoke your children, so they may not become discouraged” – don’t break your children’s spirit. The strong are commanded not to abuse their power.

Gospel: Matthew 2:13-15, 19-23

When & Where: Written around 80-90 CE, approximately 50-60 years after Jesus’ death, for a predominantly Jewish-Christian community likely in Syrian Antioch.

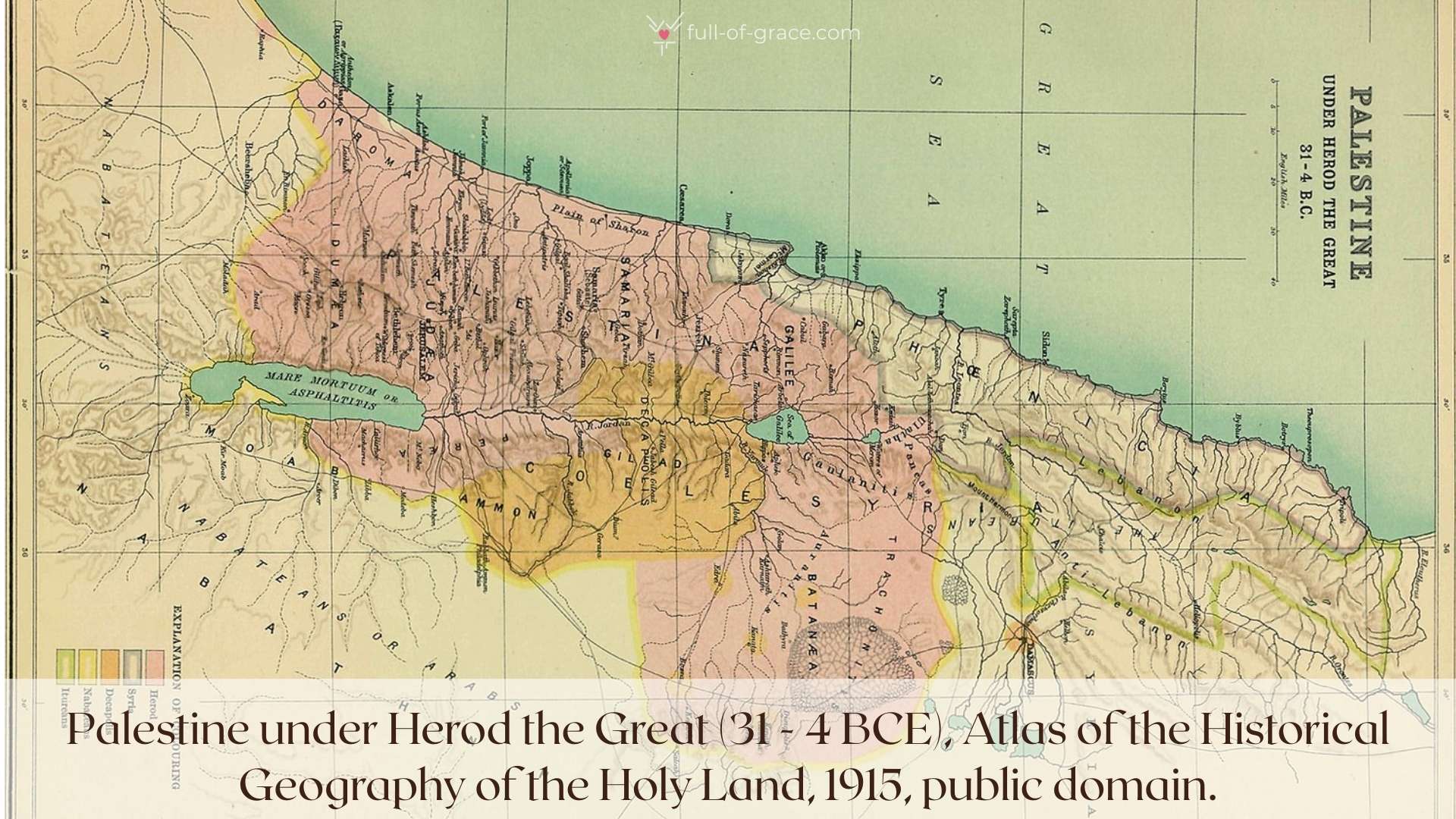

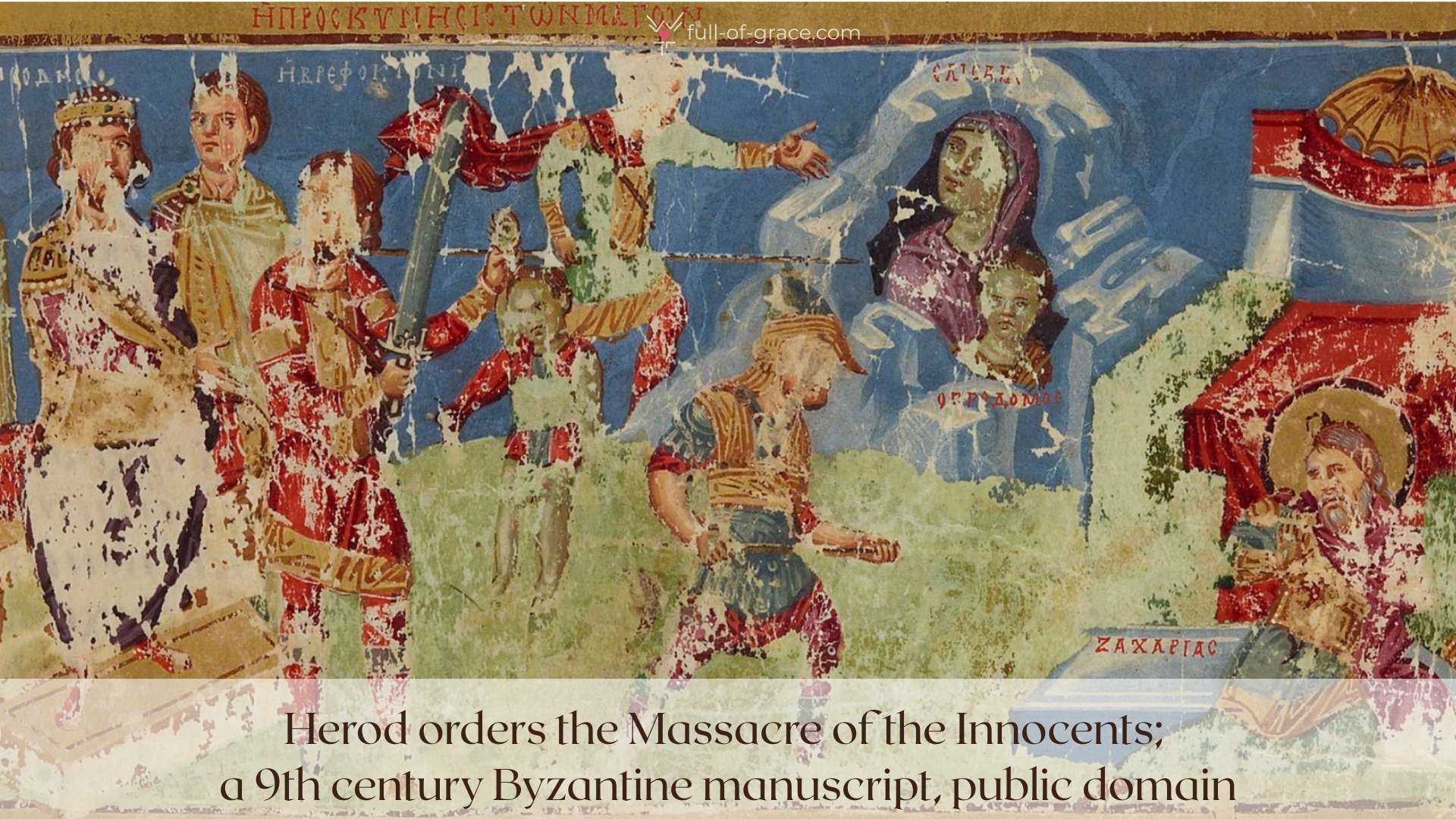

What’s Happening: This is part of Matthew’s unique infancy narrative, structured around five fulfillment quotations showing Jesus as the culmination of Israel’s story. Herod the Great (ruled 37-4 BCE) was a brutal Roman client king, paranoid about threats to his power. When he dies, his son Archelaus takes over Judea with such cruelty that Rome eventually removes him. Egypt had a large Jewish population and was the traditional refuge for Jews fleeing persecution.

Key Insight: Jesus recapitulates Israel’s history – called out of Egypt like Israel in the Exodus, returning to the land like Israel after exile. But notice: God protects the Holy Family through Joseph’s attentiveness to dreams and his immediate obedience. The Temple establishment will eventually reject Jesus, but his family receives him fully. God makes himself vulnerable, dependent on this family’s willingness to protect him, to flee, to return, to raise him in an obscure Galilean village. The Incarnation means God entrusts himself to our family systems – with all their limitations and challenges.

WHERE ARE WE?

In the Biblical Narrative: We’re in the immediate aftermath of the Nativity, before Jesus’ public ministry begins. This is the hidden life – the years when Jesus grows “in wisdom and in stature, and in favor with God and man” (Luke 2:52) within the domestic church of Nazareth.

In Salvation History: The long-awaited Messiah has arrived, but not to the Temple establishment or political powers. He comes as a vulnerable infant who must be protected, who depends utterly on his parents’ faithfulness. The covenant that was written on stone at Sinai, preserved through generations of “father and son,” now becomes flesh in a particular family.

In the Liturgical Year: Feast of the Holy Family, first Sunday after Christmas within the Octave.

THE COMMON THREAD

All four readings converge on this truth: the family is the first church, the primary place where covenant identity is formed and preserved. Ben Sira defends this against cultural pressure to hand formation over to external institutions. The psalm blesses the household where “fear of the LORD” is lived daily. Paul calls Christian families to embody splanchna compassion – visceral, embodied mercy – in their mutual relationships. And the Gospel shows us that God himself chose to become dependent on a family’s faithfulness, to be fully received first not by the religious establishment but by Mary and Joseph’s “yes.” The commandments are not preserved in stone but in the living relationship between generations – from the beginning, God has been teaching us that covenant lives in the “father and son,” in the family gathered around the table.

THE HUMAN REALITY

These readings can be difficult to sit through. If you’ve had to set boundaries with toxic family members, if “honor your father and mother” has been weaponized against you, if you’ve left an abusive relationship – these texts about family honor and submission can feel like reopening a wound. The Church needs to acknowledge this honestly.

And yet, we live in a time when many of us – perhaps rightly wounded by family dysfunction – have substituted therapeutic relationships for the messy, unboundaried work of actual family intimacy, finding it safer to process our lives with paid professionals than to risk the vulnerability of covenant commitment.

We’re living in a collision between two incomplete visions of family life:

Therapeutic culture’s blind spot: It too often treats all discomfort as trauma. It sees boundaries as always good and enmeshment as always bad. It values self-actualization above covenant commitment and struggles to distinguish between “this is hard” and “this is harmful.” The result? Marriage counseling that leads to divorce because staying is framed as “not honoring yourself.” Personal growth that systematically dismantles family bonds. A generation that bails at the first difficulty because we’ve lost the vocabulary for redemptive suffering.

Traditional family theology’s blind spot: It can romanticize suffering as “the cross” when it’s actually abuse. It confuses covenant commitment with enabling dysfunction. It doesn’t adequately recognize when systems are unredeemable, when staying would destroy you. It weaponizes “honor your father and mother” against victims. It lacks vocabulary for healthy differentiation – for the legitimate ways we need to separate from family patterns in order to become ourselves.

Neither extreme serves us. And the Holy Family offers something different – a third way.

Think about Joseph’s embodied experience in this Gospel: waking from a dream with adrenaline flooding his system, knowing he has minutes or hours to make a decision that will determine whether this child lives or dies. The gut-twisting fear of packing in darkness, not knowing if soldiers are already on their way. The exhaustion of refugees – no home, no stability, no control over when they can return.

Joseph doesn’t stay in Bethlehem out of some abstract principle of “trusting God’s plan.” He acts. He protects. He leaves. This is the crucial insight: covenant commitment sometimes requires distance. Joseph’s faithfulness to his family means fleeing from systems of power that would destroy them. He doesn’t “honor” Herod’s authority. He doesn’t submit to unjust structures. He discerns what love actually requires in this moment – and love requires getting his family to safety.

And yet, this family does what families do: they protect their own. They make a home even in exile. They teach their son their language, their prayers, their stories. When it’s safe, they return – but not to the same dangerous place. They settle in Nazareth, away from centers of power, choosing obscurity over prestige.

Notice what happens later in Jesus’ own life: he pours out splanchna compassion – that intestinal, embodied mercy – into crowds, healing and teaching until he’s depleted. And then? He withdraws. He goes to the mountain, to deserted places, to recharge in Abba’s love. Jesus models the balance we desperately need: profound engagement with others’ suffering AND the self-care that allows that engagement to continue. He doesn’t burn out because he knows how to return to the Source. He doesn’t hoard his energy because he trusts the well won’t run dry.

This is the rhythm the family is meant to teach us: the pouring out (compassion, service, bearing with one another) and the withdrawal (appropriate boundaries, rest, being replenished). Not one or the other. Both. We practice on each other – with all the messiness and failure that involves – so we can eventually live this rhythm with the world.

BRIEF REFLECTION

Today’s readings confront us with challenging questions we’d rather avoid: Who has the right to form our children? When is staying in a difficult relationship covenant faithfulness, and when is it enabling dysfunction? How do we honor parents while also growing into our own identity? When do we set boundaries, and when do we bear with one another?

Ben Sira’s world faced the seductive pull of Hellenistic education that promised advancement but dissolved covenant identity. We face similar pressures – institutions claiming authority over moral and ethical formation, offering opportunities but sometimes at the cost of the particular relationship with God we’re called to preserve. Parents today feel what ancient Jewish families felt: that the wider culture is forming their children in values they don’t share, and they have less and less say in the process.

But let’s be honest: the readings also risk reinforcing toxic patterns. “Honor your father and mother” has been used to silence abuse victims. “Wives, be subordinate” has been wielded as a weapon. “Children, obey your parents” has enabled spiritual violence. If these texts trigger you, if they remind you of harm done in God’s name – that response is valid. The Church needs to reckon with how Scripture has been misused.

The Holy Family doesn’t model perfect harmony or the absence of struggle (only last Sunday we read about their crisis) . They model something more useful: discernment in crisis, mutual respect, and two-way giving and receiving.

Joseph doesn’t demand that Mary submit to his authority – he listens to dreams, trusts her experience with the angel, protects rather than controls. Mary says “yes” to God, but it’s an informed, free consent – not blind obedience to patriarchal demand. When Jesus is twelve and asserts his own identity in the Temple (“I must be about my Father’s business”), his parents are hurt and confused – but Mary doesn’t shut him down. She “keeps all these things in her heart,” holding the tension between not understanding and not demanding he fit her expectations. Jesus returns with them to Nazareth, “obedient to them” – but this is differentiation within connection, not the erasure of self.

This is the balance: splanchna compassion (gut-level mercy) combined with appropriate boundaries. Not “honor no matter what” but “how can I love well here – which might mean distance, might mean leaving, might mean staying and bearing with difficulty.”

Sometimes love requires staying and bearing with: when there’s friction but not abuse, when growth is possible, when covenant commitments are being honored even imperfectly, when difficulty is forming us rather than destroying us.

Sometimes love requires creating distance: when someone is actively harmful, when your presence enables their dysfunction, when you can’t grow while enmeshed, when the system is breaking your spirit.

Sometimes love requires returning: when safety is restored, when repentance is real, when reconciliation is possible – like Jacob and Esau after twenty years.

Sometimes love requires permanent separation: when systems are irredeemable, when abuse is ongoing, when staying would destroy you or your dependents.

The key distinction: Discomfort ≠ Harm. Therapeutic culture often conflates these. Traditional theology sometimes ignores the difference. But they’re not the same:

- Discomfort is the friction of two distinct people learning to love each other

- Harm is the violation of dignity, safety, or capacity to flourish

The Holy Family shows us that being the “first church” means being the place where God is fully received even when the wider religious establishment will reject him. It means mutual self-giving, not unilateral submission. It means protecting the vulnerable (Joseph fleeing with Mary and Jesus) while also respecting developing autonomy (Jesus at the Temple). It means the strong using their power to serve rather than to dominate (“Fathers, do not provoke your children”).

The commandments live in us – not carved in stone but written in the relationship between generations, in the “father and son” that echoes through luchot awanim itself. This is both terrifying (what if we fail?) and liberating (God trusts us with this). God chose to become utterly dependent on one family’s discernment, protection, and love. He made himself vulnerable to our family systems – with all their limitations, all their potential for both harm and healing.

The family is where we learn to embody splanchna – that gut-level compassion that doesn’t avoid the mess but doesn’t lose itself in it either. Where we practice the rhythm Jesus modeled: pouring out in service, withdrawing to be replenished. Where we discover that covenant isn’t the absence of boundaries but the commitment to keep showing up for the discernment: What does love require here? Today? With this person? In this situation?

INTRODUCTION TEXT (Optional Reading Before Liturgy of the Word)

Today we celebrate the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph – and in doing so, we honor the truth that our families, with all their imperfections, are the first church. We hear how ancient families fought to preserve covenant identity against cultural pressure, and how God chose to become utterly dependent on one family’s faithfulness. As we listen, let us remember that the commandments were never meant to be carved only in stone – they were meant to be written in the living relationship between generations, preserved in the love between father and son, mother and child, passed on around our tables and in the hidden recesses of our homes.

EXPLORE MORE

For the history of the Feast of the Holy Family and where we are in the Christmas Octave, visit the Feast of the Holy Family (Year A) – Free Liturgical Resources post. You’ll find the fascinating story of why Pope Leo XIII established this feast in 1893, worship suggestions for embodying the family church through liturgical gestures, and practical ideas for parishes navigating this complex Sunday.

Looking for an embodied prayer experience? The Sunday Experience – A Prayer of Expanding Compassion offers a Christian adaptation of metta meditation rooted in the nativity scene. This gentle, somatic practice invites you to slowly expand your circle of compassion, beginning with the sleeping infant Jesus and moving through layers of relationship – perfect for either personal reflection or communal use as a penitential rite or post-communion meditation.

2 thoughts on “Feast of the Holy Family (Year A) – Biblical Background”